aklil(al)molook (2009), Exopalasht (2007)

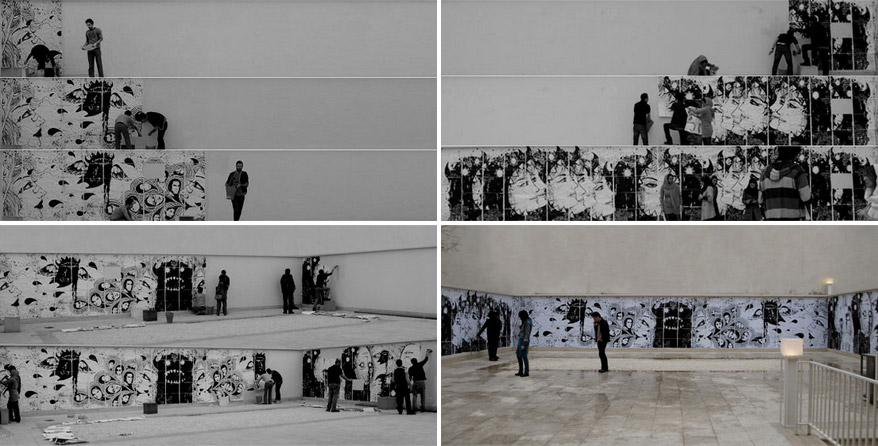

Pooya Abbasian & Farshid Monfared

Dec 2009, Mohsen gallery, Tehran, Iran. Oct 2007, Azad gallery, Tehran, Iran.

It seems that the history of Iranian painting Negargary has stemmed from three sources. The first could be conceived as the semiotic system of Iranian mysticism, which, through providing a common symbolic order between the artist and his contemporaneous audience, made the golden skies, the silver rivers, and the halos, palpable and familiar. The second was the governmental system which, by funding the artists, made room for such works to be executed – a traditional government, whose ideological and political influence, of course, could not be ignored. The third rendered a composition consisting of the social context on which the artist was grounded and the impacts of other nations on the art of that particular era. In times Chinese, in other times Byzantine or Turfan paintings each lent some of their visual elements to Iranian painting so as to be translated by Iranian painter according to his particular social context. By centuries, the audience of Iranian painting was always familiar with this triple source while knowing how to mentally reach to the subtext of the work. However, the transformation within Qajarid era – especially, the influx of modernity – severed the close ties of audience with previously accepted sources. Houses, costume, communication devices, and many other aspects of everyday life became increasingly subjected to change. If employing new visual elements seemed unaccustomed at the end of Safavid era, this time, at the eve of the new century, what appeared even stranger was the very aspiration for the survival of the language of Iranian painting. Thus, a new generation of painting emerged, carrying a false name, ‘miniature’. It attempted to retain something of the tradition while persisting to attract the contemporary audience. The golden skies, the silver rivers, the flaming trees, and the colourful birds, all became void of meaning, as a result of the disrupted link with the first source. The elements of the Ideal world as a lamé with its golden wraps pillaged were reduced to a beautiful icon replete with the nonsense. Parallel to this, the other two sources continued their tasks in a new way: The dignity of the Ideal Beauteous became a site for manifestation of mastery in plastic surgery. The eyes grew larger as the noses tended upwards. The Sormeh (Collyrium) which seemed an eternal phenomenon was replaced by a heavy make-up that could be removed at night with a cotton pad. However, curling garments and deer were still there. The result is a semiotic, and of course visual, disorder originating from the third source, which could be seen both ironically and wistfully.

Ali Ettehad

Drawing on plate, Vitrail ink on plate, Diameter 30 cm, 2010

Exhibition view at Mohsen gallery.

Exhibition view at Mohsen gallery.

It can be said that recently works of many Iranian artists are distinctive cliché. Most of them are applying traditional and national Oriental (Iranian-Islamic) patterns as a tool to attract foreign audiences. As a matter of fact some of these works quench overseas viewers thirst toward exotic are More over Exotic works are also applicable to their hypothesis about oriental artists works. As a result Western audiences pay special attention to exoticism. The theorem is neither ignoring all these achievements nor finding these artists guilty for using these symbols in their work.

The works in this exhibition are trying to criticize superficial and abusive use of these traditional patterns and national symbols and turning them to meaning-less cliché.

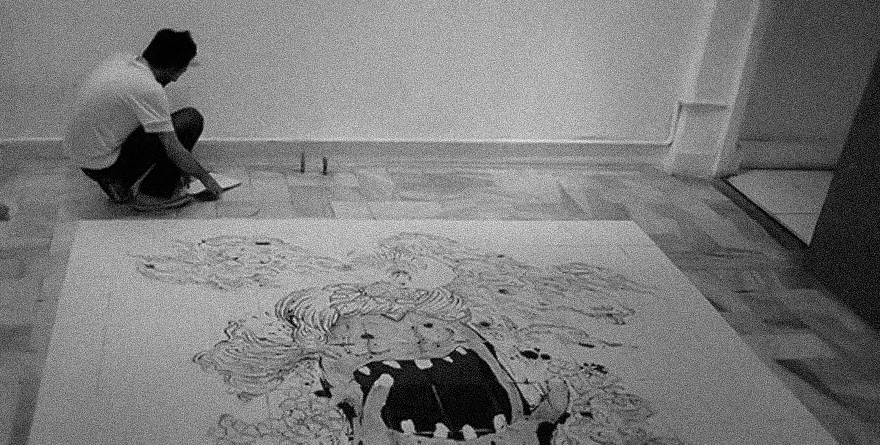

Hamid Severi

Installation of 140 A4 paper(ink on paper), 280×300 cm, 2017.

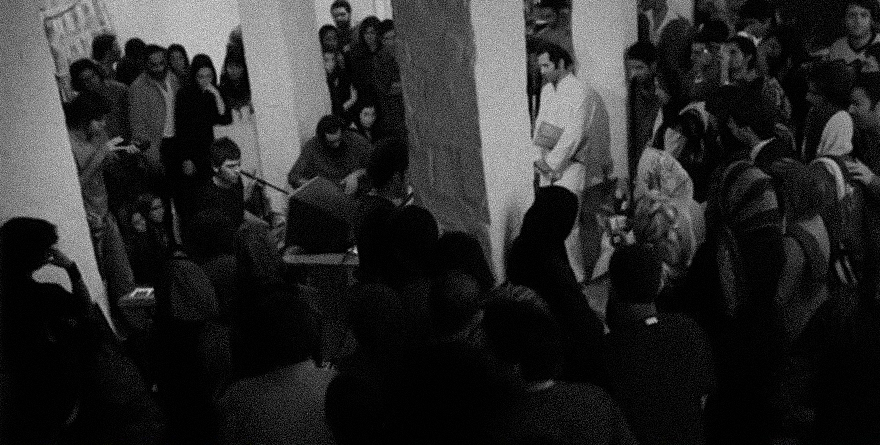

Installation of 140 A4 paper(ink on paper), 280×300 cm, 2017. Sound performance at the opening of the exhibition at Azad galley.

Sound performance at the opening of the exhibition at Azad galley.