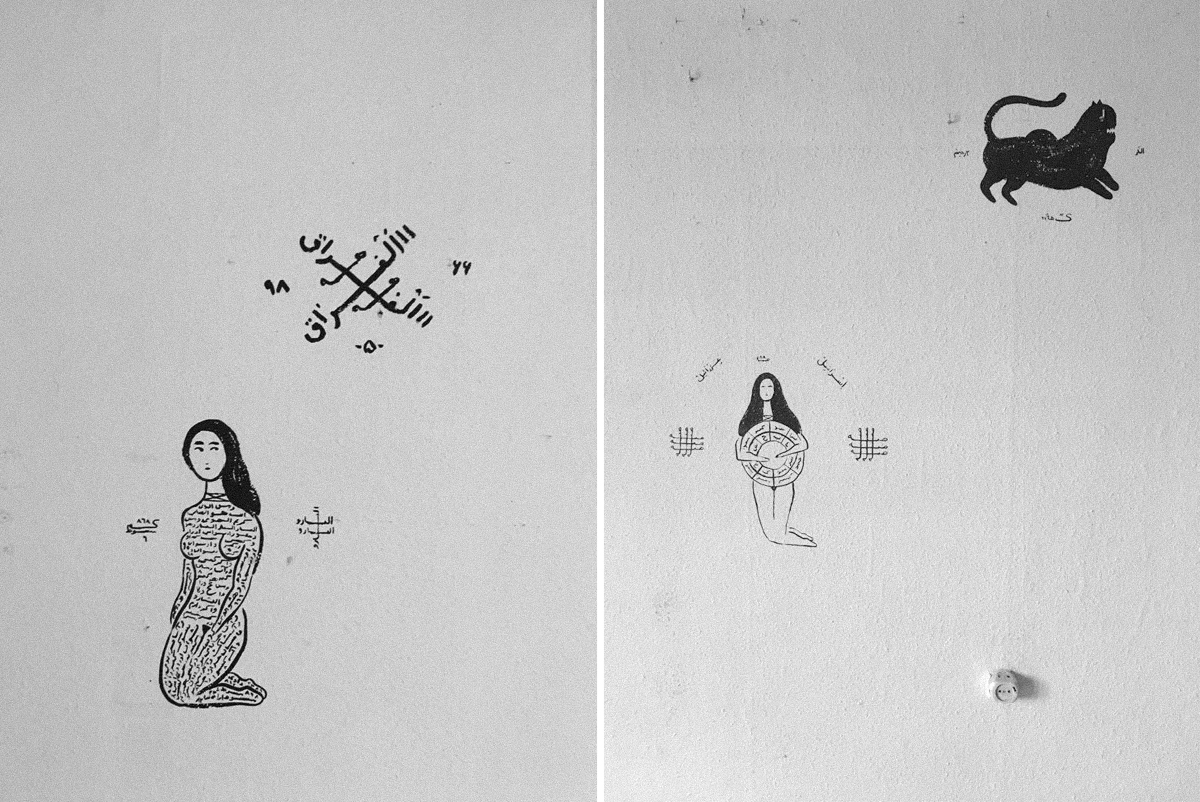

telesm, 2017

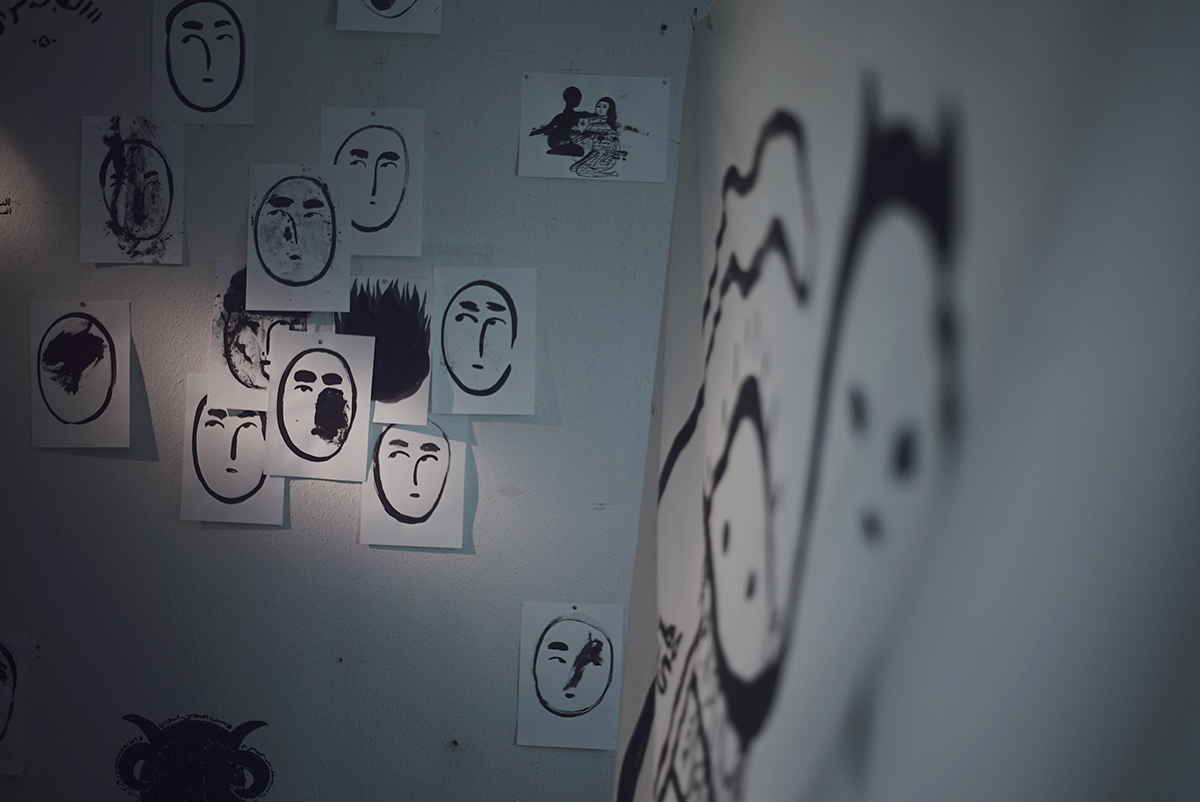

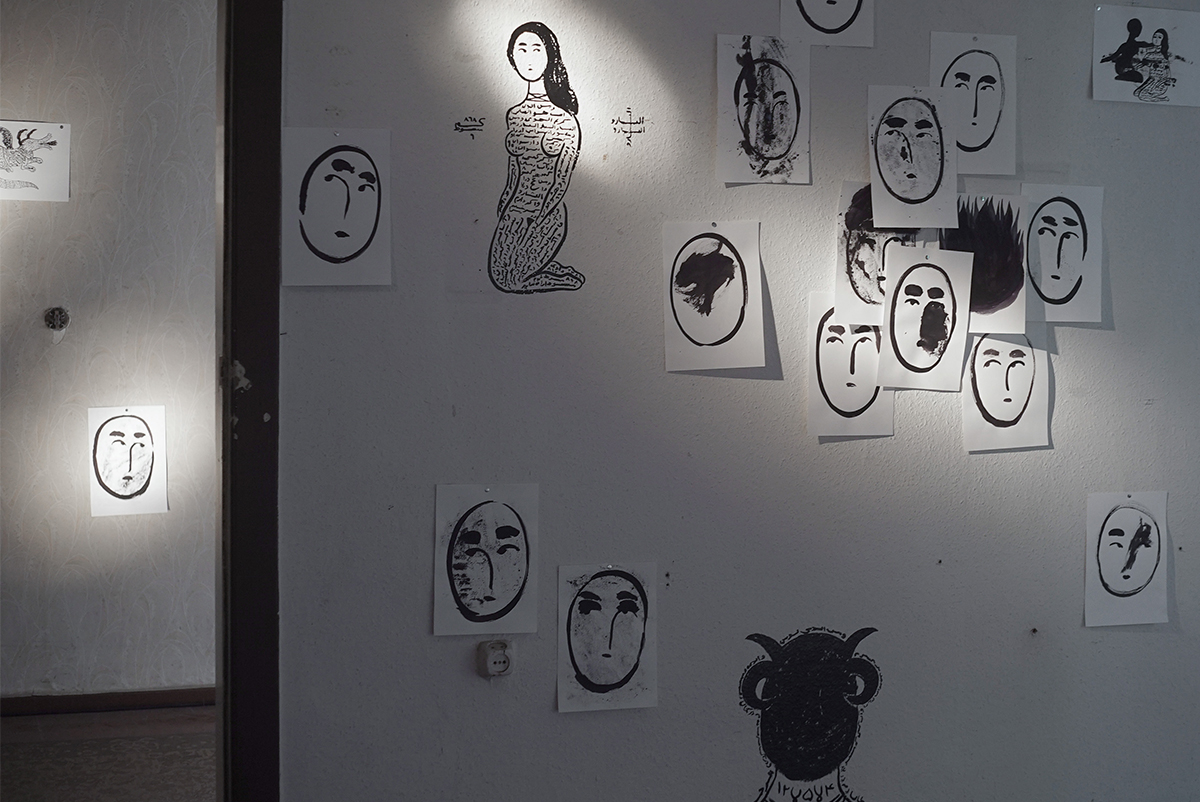

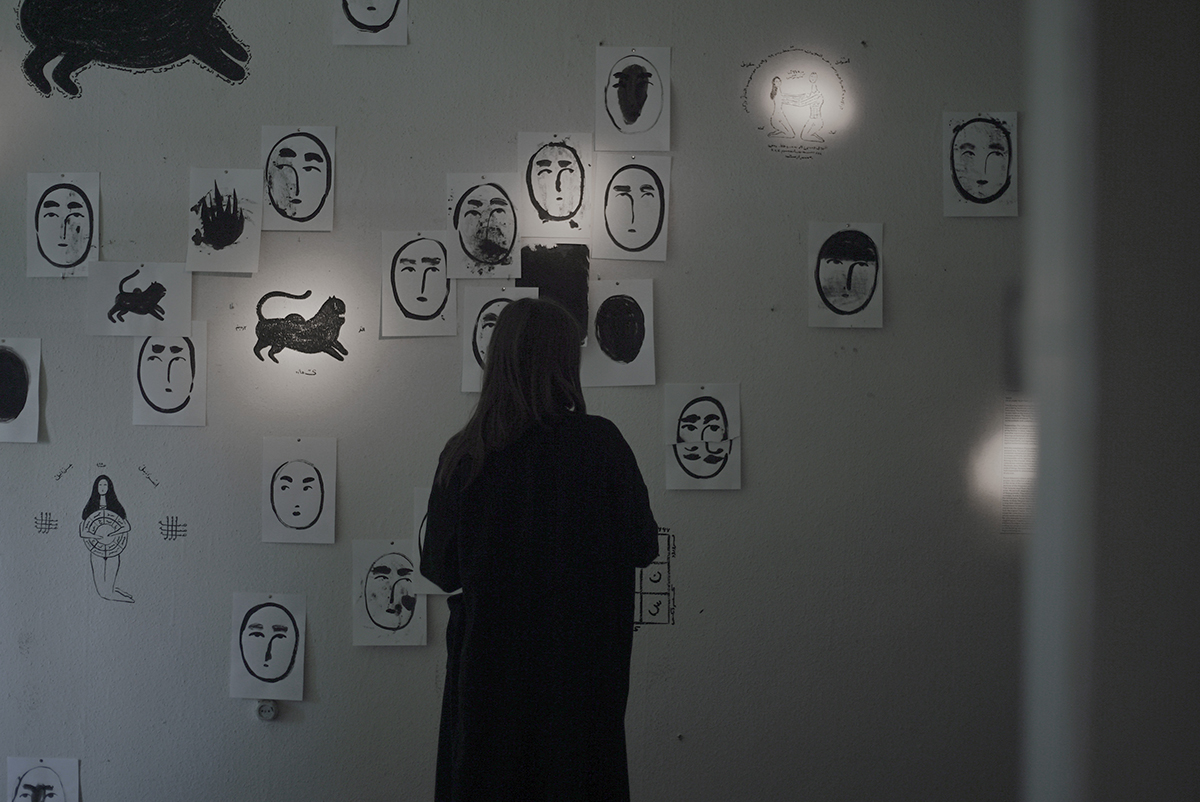

Drawing Installation (Ink on wall, paper and fabric)

Pictoplasma festival, 10-14 May 2017 at KulturKapelen, Berlin, Germany.

This drawing installation by Pooya Abbasian (born in Iran, 1983), both pervaded by mysticism and topicality, is inspired by ancient Persian talismans (telesm). Fascinated by the modernity of those drawings, Pooya Abbasian revisits them as the roots of his own practice of contemporary drawing and character design. The works exhibited today are the result of a research on plastic features of telesm. They question the artist’s origins, his status as well as the symbolic and contemporary representations of such sacred objects.

Superstition. Our cultures and religions are full of it. Superstition, through various rituals and beliefs, is a way to respond to the need for protection of the faithful. In Islam, telesm had power against the influence of demons and other supernatural beings called jinn. They were objects or simple drawings embellished with Koranic inscriptions, symbols and images, but also astrologic signs: a mix between Islamic faith and a long pagan tradition. Most importantly, and regardless of their origins, telesm are a remedy against existential anxiety and fear of unexpected events.

With this installation, Pooya Abbasian tackles a universal topic in a very personal way. His use of Chinese ink, avoiding any elaborate flourish, echoes existential metaphysical questions that superstition has always been trying to answer artificially yet efficiently. In this religious and mystical context, it’s impossible not to mention the conspiracy theories which are currently thriving on the internet. While doing research on talismans, one can quickly come across websites spreading nebulous rumors involving indifferently Illuminati, Jews, Muslims, “Freemacons” or Jesuits, all guilty of a falsified order of things. Humans need to point their finger at other people who are held responsible for phenomena they cannot understand. A need to justify at any cost. Pooya Abbasian’s telesm, acting as avatars of superstitious beliefs or pagan prayers, are a reflection of an uncertain and hateful context.

Alterity is at the center of this installation. The series of portraits echoes the fragile destinies of the imaginary victims or beneficiaries of these modern talismans. Their features result from the spontaneous inspiration and gestures of the artist. We are both observers and observed, feeling the individuality of each of these portraits. They stare insistently, inhabited by a kind of oriental nostalgia. A wink to the evil eye? A reflection on the status of the artist too.

For several years, Pooya Abbasian has been using photography, among other media, to study the gaze and its limits. The theme of voyeurism has fed a long-term research that is somehow continued through this installation. He questions his relation to the muse, his submission to the artistic intention and revives the classical debate on the position of the artist, challenger of God, the original Creator. The talisman embodies this ambiguity: its magical properties come directly from his maker, who draws a link between the secular world and the sacred sphere. Religious men were also among the very few who were able to read and write, what used to be considered as a sort of magical power. Inspired by these objects, he pays a paradoxical tribute to his origins. He celebrates his artistic and cultural heritage while putting into perspective their sacred features, suggesting he has doubts on the liberating nature of religions – as shows the cynical tranquility of this huge undulating cat.

Clementine Proby